008: Whatever happened to camp?

And why, in 2025, we need it more than ever.

The 2025 Met Gala was only 20 days ago, but by TikTok standards, it was a lifetime ago.

While writing my last piece on the theme Tailored For You, and the costume exhibition Superfine: Tailoring Black Style, I kept thinking about how I haven’t been this excited about a theme since Camp, which also got me thinking: in 2025, where did camp go?

The 2019 exhibition, Camp: Notes On Fashion, was framed around a 1964 essay from Susan Sontag titled Notes On Camp, where she described the essence of the word as a “love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration.”

Susan Sontag

Sontag argues that camp is more about how something looks or is presented than what it’s actually about. She says that pure camp is always naive, unintentional, and dead serious. Take Björk, for instance, who at the 2001 Academy Awards showed up in a gown meant to resemble a swan. It’s so bizarre, yet so perfect for her to wear something so unserious at one of the most serious events of the year — the same year Gladiator dominated the event.

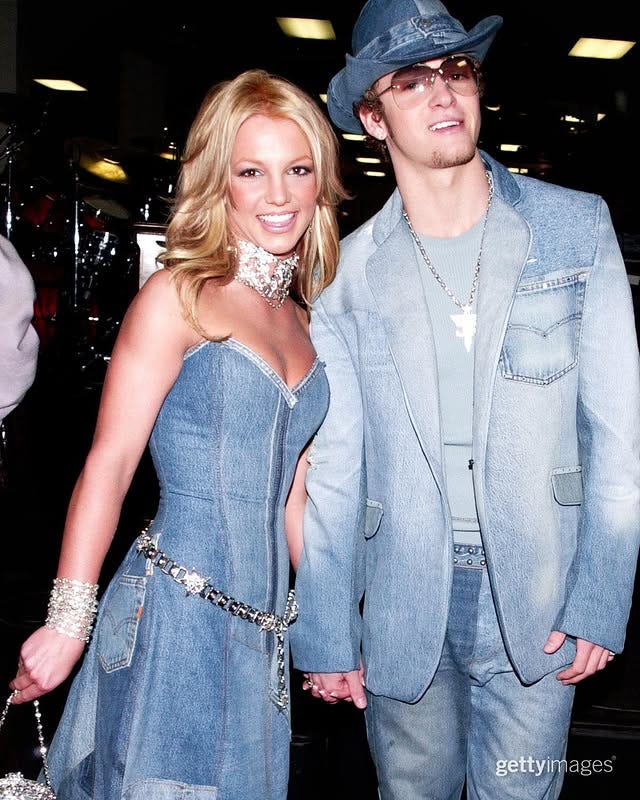

Another is Britney Spears and Justin Timberlake at the American Music Awards in 2001. The couple's look, a matching gown and tuxedo made out of denim, has only grown campier over time. It’s so fun and loud, but it’s not offending anybody. It’s joy in fashion.

Björk at the Academy Awards, 2001 / Britney Spears and Justin Timberlake at the American Music Awards, 2001

But in 2025, camp has seemed to drift away from us. Yes, we see loud and kitschy aesthetics everywhere, but they seem to be quite commercialised, always trying to sell us something. For camp to truly be camp, it has to have that naivety behind it — it has to be so bad that it is good. That is the essence of camp.

The essence of camp, according to Susan Sontag

As easy as camp is to visually point out, it’s a hard thing to explain. In her essay, Sontag says: “The whole point of Camp is to dethrone the serious. Camp is playful, anti-serious. More precisely, Camp involves a new, more complex relation to ‘the serious.’ One can be serious about the frivolous, frivolous about the serious.”

She says that “camp rests on innocence,” arguing that camp cannot exist if it’s cruel — even when it's laughing at something, it’s also celebrating it: “Camp is a woman walking around in a dress made of three million feathers.”

For me, she is Cher at the 58th Academy Awards in Bob Mackie — the extravagant headdress, crop top, sequin skirt, and abs of steel were a snub to the Academy, who she felt didn't take her seriously and hated the way she dressed. It is camp in its entirety. It dethrones the serious, but still brings an essence of joy and passion, and most of all, it “transcends the nausea of the replica,” meaning it was unlike anything we had seen before.

Cher at the 58th Academy Awards

Camp in history

The history of the word camp is often traced to 17th-century France. I didn’t do enough research into 17th and 18th-century France to know if Louis XIV and the Palace of Versailles were considered camp at the time (while the term didn’t exist, the sensibility did), but in today's standards, it fits the definition. I mean, the fact that Louis XIV had a whole posse of people dressing him up in elaborate costumes multiple times a day just to wander the palace is, to me, so camp. Marie Antoinette? The campiest of camp.

Fun little fact: The Palace of Versailles, while obnoxiously and beautifully designed, wasn’t built near a major water source. Engineers had to build enormous pumping systems to divert water from the Seine, but there still wasn’t enough water to run all the many fountains they built at once. This absurdity (innocence) amongst the frivolous is why it is so camp.

Kirsten Dunst in the 2006 film Marie Antoinette

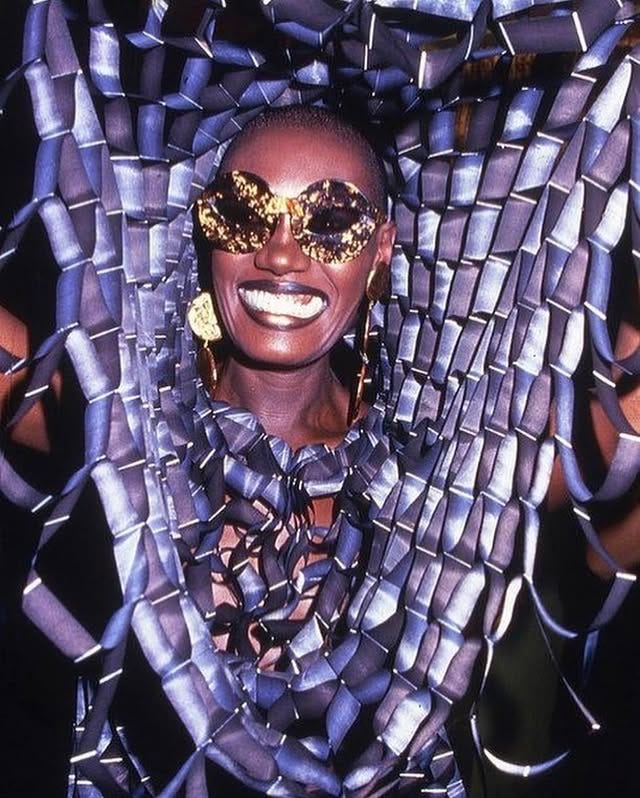

The word camp began to appear in English-language queer slang by the mid-19th century, with documented usage as early as 1909. In the 1970s and 1980s, camp thrived in queer nightlife, drag culture, and underground fashion. These communities didn’t just use camp as an aesthetic, they lived it. RuPaul, Andy Warhol and Grace Jones are just a few of many icons that embodied camp.

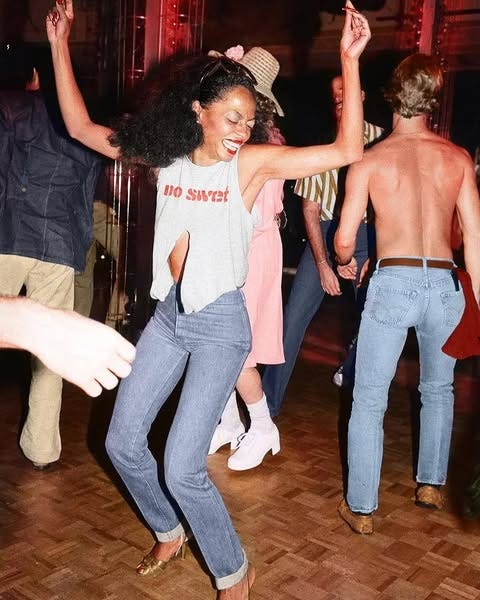

This was clear in spaces such as The Hamilton Lodge, one of the earliest known drag balls in the United States which was an important space at this time, especially for Black, transgender, and gender non-conforming people. Here, theatricality was a consistent theme. Studio 54 also opened space for performance and extravagance, known for wild disco tracks and elaborate themes and hosting some of pop culture’s biggest names like Bianca Jagger, Liza Minnelli, RuPaul, Grace Jones and Diana Ross — the campiest of campers.

Grace Jones and Bianca Jagger at Studio 54

By the 1990s, camp aesthetics entered the mainstream. Think Madonna in the iconic cone bra, famously designed by Jean Paul Gaultier (I wrote about this here), or John Galliano and his many splendid shows. Galliano frequently referenced Marie Antoinette, the Russian court, or Victorian mourning gowns, but always dialled up the volume, with large ruffles, extravagant wigs and accentuated makeup. Those designers were theatrical, referential and deliberately excessive, which are all core elements of camp. Thierry Mugler, Victor and Rolf, and Moschino under Jeremy Scott all portrayed elements of “ camp couture,” blurring the lines between art and performance, all with a collective joy.

The 2019 Met Gala

The 2019 theme and exhibition Camp: Notes On Fashion brought an array of unbridled kitsch and extravagance by the celebrity guests, some with more oomph than others. This Met Gala cemented camp’s high-fashion credibility, but the theme itself was interpreted in juxtaposing ways.

The ones who nailed the theme made us laugh and at the same time, made us question the ridiculousness of it all. “The Met Gala has always, in a sense, been an exercise in failed seriousness: for one night each year, we come together to watch celebrities try to master high fashion, try to please Anna Wintour, and try to complete the homework that the Met has assigned them. Very often they fall short,” says Rachel Syme for The New Yorker.

Lady Gaga at the 2019 Met Gala

This next quote is long, but I thought it summarised the night really well:

“The comedian and writer Lena Waithe arrived on the red carpet (actually a pink carpet) wearing a suit printed with the words ‘Black Drag Queens Inventend Camp.’ The message was clear: camp has always been a mode for marginalised people — queer people, people of colour — to reclaim the idea of taste from the dominating class; it’s about infusing great meaning into the elements of culture that people choose to discard. In that sense, it is absurd for a group of wealthy — and mostly heterosexual — celebrities to attempt to embody camp by wearing thousand-dollar gowns…

“But the essence of camp in her outfit was a typo on the jacket — ‘inventend’ instead of ‘invented.’ It was a small mistake, easy to miss, but, once you noticed, it seemed like a crack in the veneer, a reminder that so much of what we consider to be glamour is held together by boob tape and wig paste.”

Lena Waithe & Kerby Jean-Raymond at the 2019 Met Gala.

Where is camp now?

While reality TV, early Lady Gaga, and exaggerated red carpet looks have made camp hyper-visible in their own way, I find 2025 specifically at a loss. Everywhere we turn, there are absolutely elements of exaggeration and pomp, but these are often intentional amplifications of the frivolous in order to sell us something. If camp can’t exist without innocence, then these things can’t truly be camp.

Sontag wrote that “camp transcends the nausea of the replica,” but in a world saturated with hyper-replication disguised as ‘aesthetics’ and ‘cores’, and flooded with endless fast fashion knock-offs, where can camp truly thrive?

Yet this is why we need it now more than ever. Camp is a tongue-in-cheek way of looking at fashion. It doesn’t mock fashion, it mocks conventions. While conservatism creeps back into our style and ideals due to the right-leaning political landscape, we need someone brave and bold to muse and critique while at the same time bringing joy.

At the same time, Sontag notes: “It goes without saying that the Camp sensibility is disengaged, depoliticised - or at least apolitical.” I’m not saying that we need someone to be a standout against the noise and convince others to feel a certain political way. I want someone to bring joy and extravagance. I want them to question conventional norms without trying to move the world by themselves. Where is our Elton John, our Cher, our Grace Jones? I want joy and amusement to distract me from an oversaturated world that is falling apart. In 2025, there is nothing camp anymore because we’re all trying to be something we’re not.

Of course, it's not all gone and hopeless. We do see spots of glorious camp seeping through the cracks. In luxury fashion, Schiaparelli’s robot baby in their spring 2024 couture collection at Paris Fashion Week comes to mind. So does Thom Browne’s Fall 2023 couture collection. In pop culture, Doja Cat, Kim Petras and Sam Smith are who I think about when it comes to camp.

Schiaparelli Spring 2024 couture / Thom Browne’s Fall 2023 couture

There are also some current misses of camp in the fashion landscape. Duran Lantink’s Fall 2025 Duranimal collection is the latest example. His runway show featured silicone breasts on a male as the close to an otherwise brilliant show. While the show celebrated artifice, exaggeration, and theatricality, it brought a lot of controversial conversations and leaned more towards satire rather than camp. As it veers into mockery, it moves away from the idea of camp as it doesn’t have that sense of joy, but rather just shock value.

Duran Lantink FW 25/26

In 2019, Thierry Mugler told BBC Designed that camp is “freedom and fun mental health”. I miss the naivety and innocence that comes with being camp. And in 2025, more than anything, we need to bring back joy.