005: Why boho is the most coveted fashion aesthetic in 2025

Boho is thriving, but who is it really for now?

Every so often, a trend will resurface with a renewed relevance. As for the latest in sartorial cool-girl style: it is the resurgence of suede. Last week, as my coworkers debated the return of suede to the fashion consciousness, we came to one communal truth: while suede is a timeless moment, it is also a nightmare to maintain. As someone who can (and will) spill anything and everything, I have deep respect and admiration for those who put money towards a suede bag and expect it to survive.

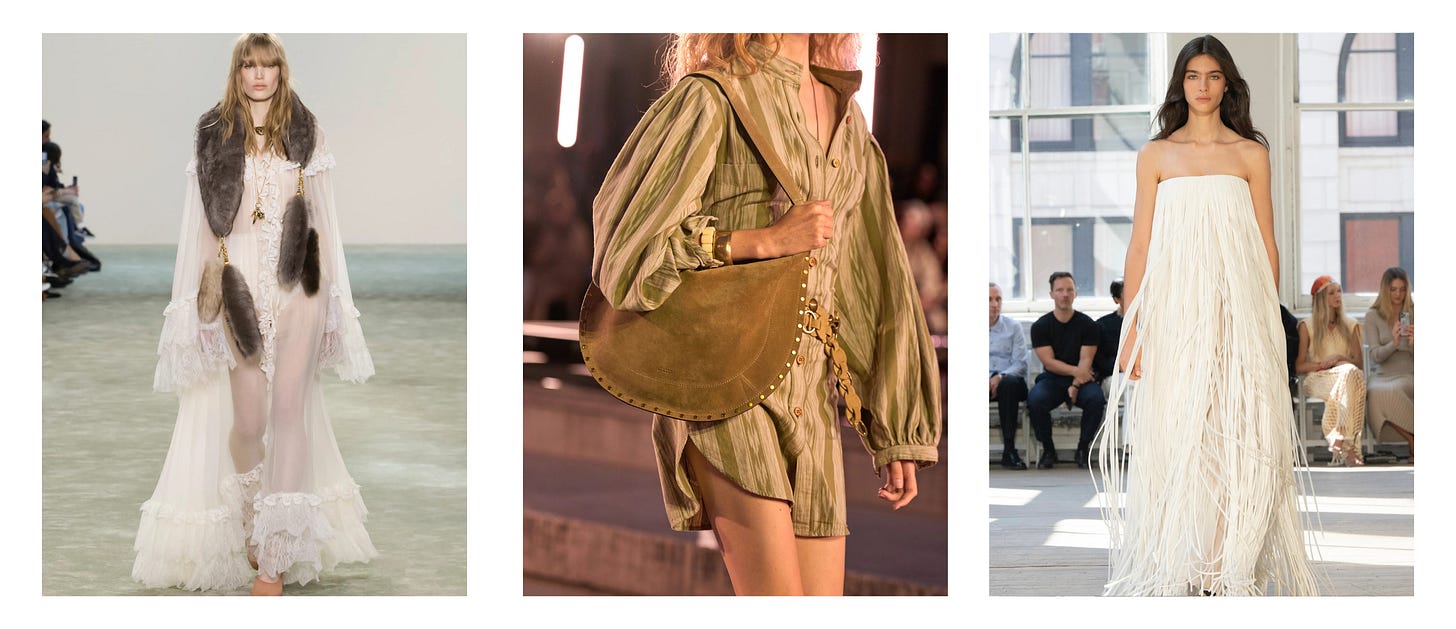

But suede is just the beginning of something bigger. Soft and flowy silhouettes with ruffles, earthy tones and blush hues have slowly appeared on the runway — a masterclass of the new bohemia spawned by Chemena Kamali’s directorial debut at Chloé FW24. One year later, paisley, pink, and fringed skirts entered fashion’s mainstream. The 2025 seasons featured suede bags at Isabel Marant and Valentino, a western rebellion from Ralph Lauren, fringe at Proenza Schouler and Erdem, and romantic, flouncy blouses at Chloé, Stella McCartney and Khaite, signalling the return of the contentious bohemian style, albeit with a modern twist.

As we enter a new age of fashion, the feminocentric style of dress has been recontextualised over the decades. Once born out of 60s liberation and 70s rebellion, then diluted into a festival aesthetic in the early 2000s, the boho style has almost lost its edge. While participation in boho style is no longer a political act and more of an aesthetic choice, I still think there is a deeper meaning behind its resurgence — and that’s exactly what I’ll be unpacking today.

The history of boho

Today’s boho style takes the current luxury approach to fashion: clean lines, muted hues, and the teasing desire for quiet luxury. This is unlike the 1960s hippie movement, which was an expression of counterculture, social change, and personal freedom. It became a means of challenging the establishment amidst the economic decline.

In the 60s, ready-to-wear was also becoming the societal norm, with couture losing its appeal as businesses appealed to the mass market. The 60s bohemian style rejected this shift of heavy consumerism, embracing natural materials and honouring slow, traditional craftsmanship like crochet, lace and knitwear. Long, flowy skirts and loose blouses with paisley and floral patterns emerged. Embroidery or lace details became the style à la mode. It stood in contrast to the era’s dominant trends: Mary Quant’s mini-skirts, space-age mod fashion, and tailored trouser suits, which were especially popular in Britain. This new counterculture produced fashion icons, Penelope Tree and Jane Birkin, among others, that embodied the bohemian spirit, blending vintage elements with textiles inspired by cultures beyond the West.

By the 70s, boho was about freedom of expression and liberation, particularly for women. Societal changes, women’s rights and an anti-conformist attitude made the unrestrictive style of dress an empowering philosophy. While boho’s roots were anti-establishment, some luxury houses were influenced by the style, notably Yves Saint Laurent (safari jackets and peasant blouses), Emilio Pucci (more psychedelic than boho, especially with prints), and Zandra Rhodes (floaty shapes, bold prints).

However, no luxury brands hold the boho style closer to their heart than Chloé. In 1952, Gaby Aghion founded the brand, bringing feminine and playful energy to the luxury stage. Karl Lagerfeld joined the house in 1963 before he was promoted to the label’s head designer in 1966. His striking prints and flowing silhouettes merged bohemian fashion with Parisian chic. They captivated a new audience who were not part of the movement but were culturally curious and wealthy.

However, it was Phoebe Philo's tenure at Chloé (2001–2006) that was most synonymous with 2000s boho-chic style, marked by smock dresses, peasant blouses, floaty silhouettes, fringe, and earthy tones. Popularised by icons like Sienna Miller, Kate Moss, and the Olsen twins, boho hit the mainstream hard and fast, while at the same time, the era of Coachella festival fashion rose with its own respective icons. Serena van der Woodsen in Gossip Girl raised a generation on Kate moss-inspired statement necklaces, midi-dresses, oversized bags and biker jackets for a little edge. Everything was a little dishevelled and unkempt but carefree.

What boho means today

Now, boho is on its third wave in 2025, and this new iteration reflects a different cultural shift. But is boho just a growing trend, or is it something more? With the looming presence of economic anxiety, AI integration, and a cultural identity crisis, today’s boho has resurged for a reason — and as a result, it feels less like a passing trend and more like a subconscious rebellion.

On her thoughts of boho making a comeback, Chemena Kamali told Vogue: “I think there’s this longing for undone-ness and freedom and softness and movement, and when you look at history, it’s rooted in the ’70s, when people wanted to free themselves from conventions and traditional lifestyles and sexuality.”

This new era of boho comes at a time when uniformity is currently dominating fashion: sharp tailoring, gender-neutral silhouettes, and structured minimalism have reigned supreme on recent runways. Corporate tailoring has reinforced a desire for practicality and protection in a gender-neutral and modest way. Boho is a romantic rejection of these sturdy, clean and structural elements: a new way of challenging the status quo and embracing personal expression. Much like 60s boho was a rejection of conformity in the late 50s and early 60s, this “undone-ness” offers an antidote to the current corporate aesthetic.

Alongside the notion of conformity also comes a discourse on ‘personal style’: a trendy narrative with a chokehold on social media. Trends like Corpcore, initially rooted in luxury aesthetics, have trickled into the mainstream as the new it-style. But as influencers gravitate toward this uniform dressing, essentially turning it mainstream, boho may be the next forward idea. But as boho gains mainstream traction again, the question is: will it follow the fate of its predecessors and become yet another uniform in itself?

While we no longer subscribe to fashion based on subcultures, fashion can still speak volumes. As economic anxiety becomes prominent and AI integration becomes the cultural norm, returning to natural materials and free-flowing fabrics can make us feel more grounded and human. The energy from these silhouettes acts as a form of escapism and can feel liberating at a time of political, social and economic distress. This is similar to the '60s and '70s, when boho fashion was an act of liberation and rejection of the government amidst economic uncertainty and women's rights. Sounds familiar!

The use of natural materials and boho style also opens up a broader conversation around sustainability. While the general public has grown tired and sceptical of greenwashing tactics, today’s version of sustainability leans more toward material integrity, craft and conscious consumption. There’s a renewed appreciation for fabrics, traditional techniques and a mindful approach to fashion, which brings us closer to nature. These clothes embody sustainability through their very construction, encouraging a deeper connection between the wearer and what they choose to put on, offering a tactile, grounded connection to sustainability without needing to say the word at all.

In an era lacking defined subcultures, bohemia may offer the opportunity for subtle performance: a way of dressing that rejects the status quo and aligns with your beliefs in a quiet rebellion. It’s not just about looking different, but about feeling different, too.

As Chemena Kamali put it: “This longing for (boho) comes from wanting to feel that spirit once more… It’s the moment for it again: People want to be themselves, live the way they live — defining your life for yourself.”